Rumunia - Romania - România

The Paradox of Nostalgia Over Communism

Publication: 15 October 2021

Rumunia - Romania - România

The Paradox of Nostalgia Over Communism

Publication:

TAGS FOR THE ARTICLE

TO THE LIST OF ARTICLESOne of the most surprising lessons that I was taught in the field of nostalgia was that it is not necessarily rooted in the past, as I kept thinking for the longest time. I absolutely disregarded the role that the future plays here, and to be more exact – the way we think about our future.

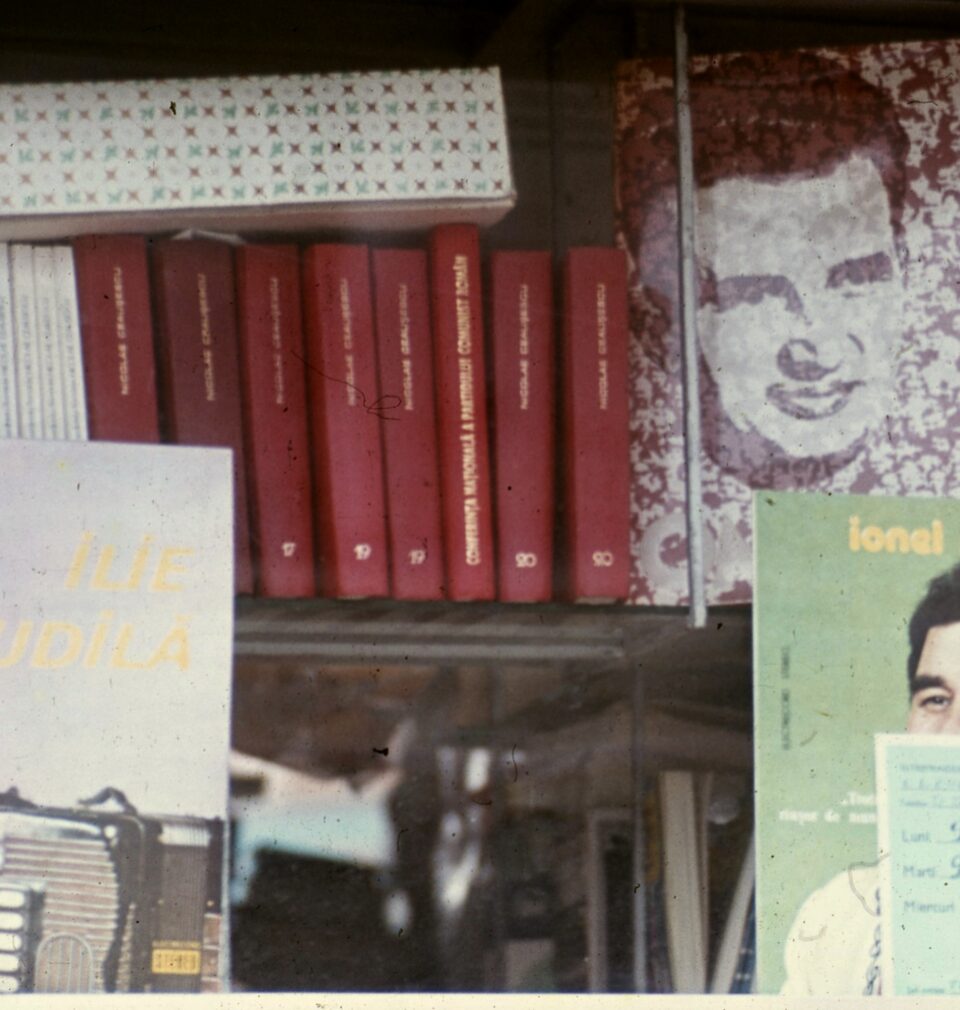

“I am an old communist hag!”

I was 20 when the dictatorship collapsed. I came from a family where the spirit of anti-totalitarianism was present in everyday domestic life. As far back as I can remember, my father was a zealous anti-communist and my mother tried to – although without putting much faith in it – temper his views so that he wouldn’t get us in trouble. Finally, when the euphoria over the collapse of the regime had finished and after the Ceauceșcu’s were executed by a firing squad, we all hoped for a new world – pure and just, and born overnight. That naturally never happened. Not only were our hopes never fulfilled but what’s more, over the period of several years, a new human species (very odd, in my opinion) evolved – whining and muttering rather than speaking – the nostalgic people. Those who wished Ceauceșcu’s regime hadn’t been abolished, life seemed better under the dictatorship. Initially I didn’t take them seriously. I thought they used to be members of the old regime (the “nomenklatura”) or the Securitate (the secret police) or otherwise they were mentally disturbed. I wasn’t able to come up with any sound reason for a sane person to feel nostalgic over the time they were forced to queue for food or suffer from cold, and when every single word they uttered made them live in fear. One day I encountered an older lady who told me – in a very precise and honest manner and with a great deal of enthusiasm that I naturally failed to share – all about her longing and about her life under communism. The very memories that made me feel indignant and horrified, made her cheeks flush with emotion.

I realised that we lived on two different planets. There was no understanding between the two of us as our perception of things differed fundamentally. And then this sudden thought occurred to me, which has changed my whole attitude: had I been through everything – absolutely every single thing – that this older woman had to go through, wouldn’t I think the way she does? Do I have right to judge her or hold her in contempt just because my life took a different path and I didn’t spend as many years under dictatorship. I decided to listen carefully to what this woman had to say and try to understand her. Several years later, I started writing a book based on such kinds of experiences in which I attempted, among other things, to reconstruct the mechanisms of paradoxical nostalgia. This is how my book Sunt o babă comunistă (I Am an Old Communist Hag), which was published in 2006, originated. I gained much insight into totalitarianism when working on this book, but what helped me understand it even better were conversations with my readers from various countries in which the translations of my book were published. I won’t go on here with the story of the retired lady I wrote about in the book, but I would rather like to try sum up the discussions on nostalgia that my novel brought forth over a few years. The roots of this very peculiar nostalgia is what interested me most, so I am going to focus on this.

Nostalgia – figuratively speaking

It seems that the most common explanation of this phenomenon and the one that is most often brought up refers to nostalgia over the years of one’s own youth. Looking back at their life, people mix together – without giving it much thought – the state of youthful vigour (or that of the age of adolescence) with the socio-cultural context of the period. At the same time, they let the latter shine with borrowed light, just like the moon reflects the light of the Sun. Thus, according to the logic of emotions, any (auto)biography must blot out historicity and blur the social and political background in focusing on the individual. The state of being weak, helpless or possibly dependent on others – all of which is indispensably connected with ageing – stands in contrast with the former vitality and vigour and makes one see their past through intensely rose-coloured glasses. Ironically, the abandonment of the sole ideology cultivated by the system that valued the collective more than the individual – namely, the dialectical materialistic ideology – is the only thing that can now save this system by means of the mechanisms of nostalgia.

People are forced to administer their self-image and self-esteem when exploring their past. What enabled me to look at this problem from more than a purely theoretical perspective, was a violent outbreak of honesty on the part of one of my female readers. “What am I supposed to do with over 40 years of my life? Toss it into a rubbish bin?” – she asked. “If absolutely everything was wrong back then, it means that my life was useless. I cannot remove 40 years from my life as if nothing ever happened. You cannot assume that your life was worth nothing. All the joyful moments that you once experienced demand their right to recognition.” Those joyful moments – less or more numerous – regardless of the quantity – demand more than mere acknowledgement – in fact they demand to be blown out of proportion and at times to be simply invented. In uncertain times they give meaning to life that is largely controlled by the system. The meaning, which gets reconstructed from the present perspective, is necessary to save people from emotional breakdowns and ensure that they are able to communicate with others.

Yet another interesting metaphor that I came across has to do with poisoning. If totalitarianism is a toxic substance whose homeopathic doses are breathed in daily with the air, drunk in the water or taken from any other source for over 40 years, then one is just a sick man who needs to go through detox and receive specialist care after the collapse of the regime. Nostalgia is resistance against the effort of healing. It is a natural reaction of the patient who grew accustomed to the poison; a reaction of the sinner who is unable to break the addiction. In my opinion, this metaphor is more interesting when used by people to talk about themselves rather than to condemn others. Only when speaking of themselves, do they reveal their inner struggle – the struggle they have to fight alone, practically abandoned by the post-communist system. Specialist care would then be expected during the rehab period.

Nostalgia understood as a failure to adapt occurs quite frequently in its simpler or more complicated version. In my opinion, it can be really interesting when viewed through the magnifying glass of daily life. People who used to live in a totalitarian society needed several years to adapt, to learn how to cope, to know the ropes of this system and to be able to support themselves. Based on the resources that were available, they made up their ambitions and planned their professional careers. Just like plants growing towards the sunlight, they evolved following the “sunlight of their world”. It was a malfunctioning society, dominated by fear and suffering privation, yet its members were well familiarised with the rules of the system. They built some kind of normality for themselves and enjoyed the comfort of it, low as it were. The regime then collapsed and the world around them has drastically changed (its coordinates). Elation over the fall of dictatorship inevitably carries with it the discomfort of having to adjust to a new world, with new rules, possibilities and resources to follow. It is much easier for younger people to adapt as they go but older people are disoriented, unable to learn and find themselves deprived of something that is commonly known as life experience, which is normally a source of great pride – specifically to the elderly. In order to counteract this painful state, they return to the stability of their previous identity and since it is not achievable within the existing societal order, they need to resort to their memories to reconstruct this state in the virtual reality. The discourse of nostalgia creates a parallel universe in which those who are maladapted or dispirited can meet and feel secure for a short time.

Following this interpretation I was introduced to an explanatory version, somewhat risky in my opinion, but still attractive in its sophisticated understanding of nostalgia among the elderly. It is well known that totalitarian societies are strongly hierarchised and gerontocratic with age being one of the main access codes to decision making, resources and social advancement. Old age is associated with experience, competence, wisdom and trust or loyalty. People brought up within this system of values expect to enjoy wide recognition from society when they reach a certain age. Let’s imagine that at the final stage of this process of accumulating recognition from society, the frame of reference suddenly changes entirely and now it is the young – associated with vitality, creativity and the ability to change who become the privileged group in this new world. The life of concealed expectations, which – being an intrinsic part of the cultural code so to speak – are barely intentional, gets betrayed by history. Thus, nostalgia appears so that the expectations that were betrayed on a social level can get evened out on a psychological level.

One of the most surprising lessons that I was taught in the field of nostalgia was that it is not necessarily rooted in the past, as I kept thinking for the longest time. I absolutely disregarded the role that the future plays here, and to be more exact – the way we think about our future. People nostalgic for the old regime would be those who cannot find their place in a newly arising world, who are unable to re-define their project in a new context. Sensing that there’s no future for them, they withdraw to the past. It is often the elderly who find themselves in such a situation, although it can also affect other socially disadvantaged people, like the long-term unemployed. The post-communistic world has been more concerned with the division of resources than with forming a comprehensive social policy; it was focused more on condemning people rather than communicating with them so the number of nostalgic individuals was always fairly high and peaked in times of economic recession.

A few final numbers

Christian W. Haerpfer[1] provided a detailed analysis of the 1990s (in Romania). According to him, half the population of Romania were dissatisfied that the centralised communist economy was gone. It was not a large number compared to Hungary where the percentage of dissatisfied citizens reached over 70 per cent or to the Ukraine where it exceeded 90 per cent. In Romania, the percentage of people feeling nostalgic over communism as a political regime reached around 20 per cent in the 1990s which was below the Eastern European average, whereas in Hungary as well as the states of former Soviet Union it reached 50 per cent.

The number of nostalgic individuals increased considerably when the economic recession started. A survey from 2010 conducted by the Romanian Institute for Evaluation and Strategy (IRES) shows that 63 per cent of the Romanian population believes that life in Romania was better under Ceauceșcu and 68 per cent claim that the communist regime was a proper ideology which was however, incorrectly implemented. In the opinion of 49 per cent, Nicolae Ceauceșcu was a good leader and 67 per cent hold that Elena Ceauceșcu was a weak leader. Finally, 37 per cent truly wish that communism hadn’t fallen. According to a poll conducted by the Romanian Center for Public Opinion Research (CSOP), also from 2010, 49 per cent of the population aged 15 and older think that life before 1989 was better than it is now.

Translated from the Polish by Agnieszka Rubka-Nimz

***

[1] Christian W. Haerpfer, Democracy and Enlargement in Post-Communist Europe. The Democratisation of the General Public in Fifteen Central and Eastern European Countries, 1991–1998, [eBook], London and New York 2002.

Copyright © Herito 2020